Deploying Stateless Microservices: Introduction

Using Services to Expose Applications

The way we accessed the Pod is not very practical. It's helpful for quick testing and debugging, but it's far from being a production-ready solution. As mentioned earlier, a Pod is a transient resource. If the Pod crashes or is deleted, we would lose access to the application. Moreover, if we have multiple replicas of the Pod (which we do), we would need to set up port forwarding for each one, which is not feasible. A solution to this problem is to use the different types of Services that Kubernetes provides.

ℹ️ A Service is an abstraction layer that provides an access point to a set of Pods. It acts as a stable endpoint (IP address and DNS name) for accessing the Pods, even if the underlying Pods are created, deleted, or rescheduled. Services enable communication between different components of an application, as well as between applications running in different namespaces or clusters.

In Kubernetes, there are different ways to provide access to applications running in Pods. Some of the most common types of Services include ClusterIP, NodePort, LoadBalancer, and Ingress. In this section, we will explore how to create these different types, what they are used for, and their pros and cons.

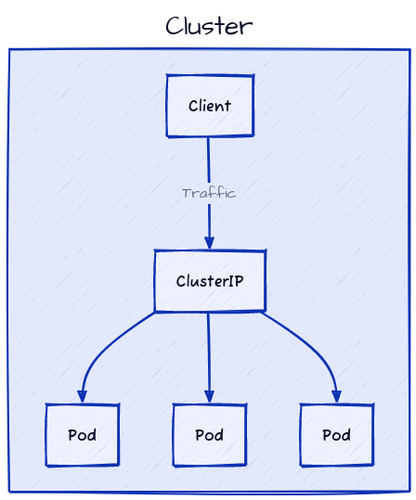

ClusterIP Service: Internal Communication

Let's suppose we have deployed a frontend microservice in the same Namespace as our Flask API. The frontend needs to communicate with the backend API to fetch and display data. To enable this communication, we need to create an internal gateway between the two services. This is where a ClusterIP Service comes in handy.

ClusterIP is the default Service type that provides a stable virtual IP to reach a set of Pods within the cluster (within the same Namespace or across different Namespaces). Using a ClusterIP Service, the 3 Pods we created earlier can be accessed through a single DNS name, which is the name of the ClusterIP Service.

If we had two nodes in our cluster, the ClusterIP would be reachable from both nodes and could even be used to reach the Pods from other Pods running on different nodes. In other words, if a request is sent to the ClusterIP on NodeA and the Pods are running on NodeB, the request will be routed to NodeB and then to one of the Pods.

The ClusterIP

This is how to create a ClusterIP for our Service:

cat < kubernetes/cluserip-service.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: stateless-flask-clusterip-service

namespace: stateless-flask

spec:

type: ClusterIP

selector:

app: stateless-flask

ports:

- port: 5000

protocol: TCP

targetPort: 5000

EOF

apiVersion: The version of the Kubernetes API to which this manifest adheres.kind: The type of Kubernetes object this manifest describes. In this instance, it'sService.metadata: Metadata about the Service, including its name and Namespace.spec: The Service's specifications, including its type, selector, and ports.type: ClusterIPindicates that this Service is a ClusterIP Service. If we remove this line, it will default to ClusterIP (default behavior).selector:defines a selector identifying the Pods this Service should route traffic to. Here, it selects Pods with the labelapp: stateless-flask. This label must match the labels defined in the Pod template of the Deployment.ports:outlines the Service's port configuration. Here, we define a single port mapping:port: 5000is the port that the Service will listen on.protocol: TCPspecifies the protocol used by the port (TCP in this case). This is the default protocol and can be omitted.targetPort: 5000is the port on the Pod to which traffic should be sent. This must match thecontainerPortdefined in the container specification of the Pod.

Apply the YAML file and check the list of Services:

# Apply the ClusterIP service

kubectl apply -f kubernetes/cluserip-service.yaml

# List the services

kubectl get svc -n stateless-flask

To access the Service, we can use port forwarding again. This time, we will forward the Service port to our local machine.

# Kill any process running on port 5000

fuser -k 5000/tcp

# Port forward the service port 5000 to local port 5000

kubectl port-forward svc/stateless-flask-clusterip-service 5000:5000 -n stateless-flask > /dev/null 2>&1 &

Now, we can test the connection to the Service using a curl command.

# Test the POST request

curl -X POST http://0.0.0.0:5000/tasks \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"title": "Kubernetes", "description": "Master the art of using containers, Kubernetes and microservices"}'

# Test the GET request

curl http://0.0.0.0:5000/tasks

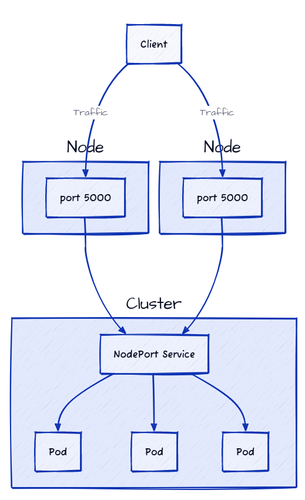

NodePort Service: Good but Not Ideal

Instead of using port forwarding, we can expose our Service externally using a NodePort Service. This type of Service exposes a Deployment externally on a static port on each node in the cluster. The port range for NodePort Services is 30000-32767, which allows external traffic to reach the Service on the specified port, which is then forwarded to the Pod.

ℹ️ Service NodePorts can only be in a "special" port range (30000-32767) due to several reasons, including not interfering with real ports on the node and avoiding random allocation conflicts.

The NodePort

The following YAML creates a NodePort service for our microservice:

cat < kubernetes/nodeport-service.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: stateless-flask-nodeport-service

namespace: stateless-flask

spec:

type: NodePort

selector:

app: stateless-flask

ports:

- port: 5000

protocol: TCP

targetPort: 5000

nodePort: 30000

EOF

The configuration is very similar to the ClusterIP service, with a few differences:

type: NodePortindicates that this Service is a NodePort service.nodePort: 30000specifies the static port on each node where the service will be exposed. If this field is omitted, Kubernetes will automatically assign a port from the default range (30000-32767).

You can now apply the YAML file:

kubectl apply -f kubernetes/nodeport-service.yaml

List the services:

kubectl get svc -n stateless-flask

Get the external IP address of any node in your cluster:

EXTERNAL_IP=$(kubectl get nodes -o wide \

-o jsonpath="{.items[0].status.addresses[?(@.type=='ExternalIP')].address}"

)

Using your web browser, you can now access the service using the external IP address and the NodePort (30000):

# Test the GET request

curl http://$EXTERNAL_IP:30000/tasks

If we had multiple nodes in our cluster, we could use the external IP address of any node to access the service. The request would be routed to one of the nodes, which would then forward it to one of the Pods. Even if the Pods are not running on the node we are accessing, the request will still be routed correctly.

One of the advantages of NodePort is its simplicity, as it doesn’t require any external network components. It’s also easy to use and doesn’t require much configuration.

However, there are some drawbacks to using it:

- It is not very secure since we need to make our nodes accessible from the internet if we want to access the service externally. This increases the attack surface of our cluster.

- It is not very efficient since all traffic to the service must go through the node, which can create a bottleneck if there is a lot of traffic.

- It is not very flexible since we are limited to a specific port range (30000-32767) and cannot use standard ports like 80 or 443. This can be problematic for some applications.

- It is not very user-friendly since users need to remember the port number to access the service.

- It’s not ideal for dynamic environments where nodes may be added or removed frequently and their IP addresses may change.

NodePort can be useful for testing and debugging purposes. However, if you have a production workload and you want to allow external traffic, it is not the most suitable solution.

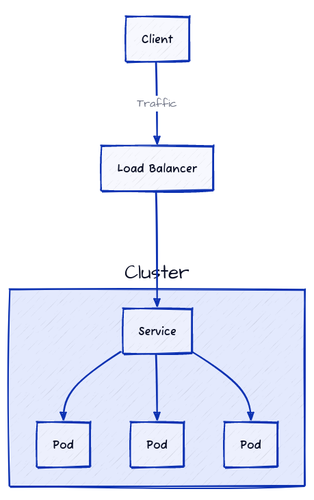

LoadBalancer: How, When, and Why to Use It

NodePorts were designed to be used in conjunction with an external network load balancer. You open a port on each node while keeping these nodes in a private network, and then you configure an external load balancer to route traffic to the nodes on that port. With this type of service, you have a single entry point to your service, which is a better approach than exposing each node directly. NodePorts were designed to build LoadBalancer services on top of them. They are not supposed to be very friendly to humans because humans are not the target audience.

Like load balancers in traditional IT infrastructure, a LoadBalancer service in Kubernetes distributes incoming network traffic across multiple backend Pods (through NodePorts) to ensure not only external accessibility but also the high availability and reliability of applications. In addition, it provides a single point of access to the service, which simplifies the management of network traffic.

When you create a LoadBalancer service, two components are created:

- The load balancer machine (external to the cluster)

- A LoadBalancer service used to configure the load balancer and to represent it inside the cluster.

If you are using DigitalOcean, AWS, GCP, or any other cloud provider, creating a LoadBalancer service will automatically provision a load-balancing machine for you. This is done using the Cloud Controller Manager, which is responsible for managing cloud-specific resources in a Kubernetes cluster. The CCM (Cloud Controller Manager) interacts with DigitalOcean APIs (in our case) to create and provision the load balancer with the right configurations.

If you are using a bare-metal cluster, you will need to use a third-party load balancer like MetalLB to provide LoadBalancer services.

The LoadBalancer

To create a LoadBalancer service, use the following YAML:

cat < kubernetes/loadbalancer-service.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: stateless-flask-loadbalancer-service

namespace: stateless-flask

spec:

type: LoadBalancer

selector:

app: stateless-flask

ports:

- port: 5000

protocol: TCP

targetPort: 5000

EOF

Here, the only difference from the NodePort service is the type: LoadBalancer field, which indicates that this Service is a LoadBalancer service. The nodePort field is omitted because it is automatically assigned by Kubernetes.

Run the apply command:

kubectl apply -f kubernetes/loadbalancer-service.yaml

Watch the list of your services using kubectl get svc -n stateless-flask -w. When the external IP address of your Load Balancer is ready, start testing the API using the same IP and port 5000 (port).

Let's test:

# Wait until the EXTERNAL-IP is assigned to the LoadBalancer service

while [ -z "$LOAD_BALANCER_IP" ]; do

echo "Waiting for the LoadBalancer IP..."

sleep 5

LOAD_BALANCER_IP=$(kubectl get svc stateless-flask-loadbalancer-service \

-n stateless-flask \

-o jsonpath="{.status.loadBalancer.ingress[0].ip}")

done

# Test the API

curl http://$LOAD_BALANCER_IP:5000/tasks

# We can delete the LoadBalancer service when we are done testing

kubectl delete -f kubernetes/loadbalancer-service.yaml

One of the significant advantages of using a Load Balancer is its ability to automatically detect unhealthy replicas and redirect traffic to healthy ones, adding another layer of reliability to your workload. Additionally, when you create a LoadBalancer, you can add advanced features like SSL termination, session persistence, and health checks.

However, there are some drawbacks to using a Load Balancer. A LoadBalancer Service in Kubernetes works at the network (Layer 4) level, meaning it can forward traffic based only on IP address and port, not on what’s inside the request. An LB can’t make decisions based on HTTP headers, paths, or other application-level data — it simply says "send everything arriving on this port to the Pods behind this Service." It doesn’t understand HTTP, URLs, or headers — it just moves packets around. As a consequence, if you have multiple Deployments (e.g., app1 and app2) running in the same cluster and you want to redirect traffic from /app1 to app1 and from /app2 to app2, you can’t reuse the same LoadBalancer to expose them. Each Deployment would need its own LoadBalancer, which can become costly and inefficient.

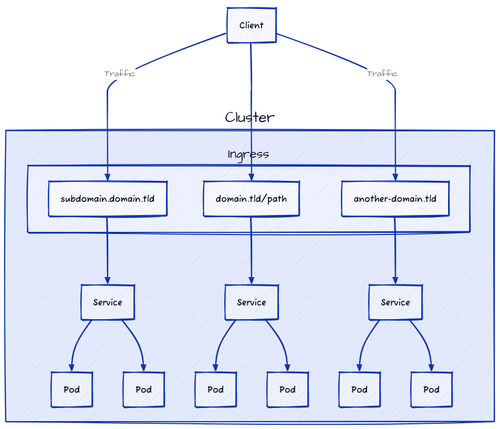

Ingress: Smart Routing at Layer 7

HTTP routing (based on paths, hostnames, or TLS rules) happens at Layer 7, the application layer. Looking at the OSI model, we have 7 different layers, each responsible for specific functions in network communication:

- Physical Layer

- Data Link Layer

- Network Layer

- Transport Layer

- Session Layer

- Presentation Layer

- Application Layer

At the physical layer, we deal with hardware components like cables and switches. The data link layer manages the transfer of data between devices on the same local network. The network layer routes packets across different networks. The transport layer transfers data between systems using protocols such as TCP or UDP. The session layer establishes, manages, and terminates communication sessions between applications. The presentation layer translates data formats (e.g., encryption, compression) for the application layer, which is where end-user applications operate.

We are primarily interested in Layer 4 and Layer 7. Let's imagine this scenario: We have two applications deployed in our cluster, app1 and app2 (using 2 different Deployments), and we want to expose them using the same domain name but different paths:

domain.com/app1-> routes toapp1domain.com/app2-> routes toapp2

We would usually point the domain.com A record to the external IP address of the LoadBalancer Service we created earlier, and we would expect the LoadBalancer to route the traffic based on the path.

However, since LoadBalancer Services in Kubernetes operate at layer 4 (Transport Layer), they understand IP addresses and ports, but not the content of the traffic itself. To it, all traffic arriving at a specific IP and port is treated the same way, whatever the HTTP request details are. For example, domain.com/app1 and domain.com/app2 for a layer 4 load balancer are indistinguishable because they both resolve to the same IP (where domain.com points) and the same port (80 in our case).

In contrast, layer 7 (Application Layer) load balancers have visibility into the full HTTP request, including paths and headers. This allows them to make intelligent routing decisions based on the request’s content. An Ingress service can route domain.com/app1 to the Pods of app1 and domain.com/app2 to the Pods of app2 since it terminates the HTTP connection first, inspects the request, and then takes action based on a set of defined rules (e.g., path-based routing).

Technologies like NGINX Ingress, Traefik, HAProxy Ingress, Istio Ingress, and others are examples of Layer 7 load balancers that can be used to implement this functionality inside Kubernetes clusters. We refer to them as Ingress controllers.

When you install an Ingress controller, Kubernetes gives it a public door by creating a LoadBalancer Service. The cloud provider ties an external IP to that door, and traffic flows straight to the Ingress controller Pods.

The controller looks at the Ingress rules you defined and sends each request to the right Service inside the cluster (typically a ClusterIP Service).

Client (web browser)

↓

LoadBalancer

↓

Ingress Controller (Pod) ← Ingress Resource (Rules)

↓

ClusterIP Service (Service)

↓

Pods

The Ingress

Before creating the Ingress, let's clear all the resources we created so far to keep our cluster clean and avoid any confusion:

kubectl delete -f kubernetes/nodeport-service.yaml

kubectl delete -f kubernetes/loadbalancer-service.yaml

kubectl delete -f kubernetes/cluserip-service.yaml

As we have seen, an Ingress controller routes traffic to a Service. If we want to expose our Flask application using an Ingress controller, we first need to create its corresponding Service. In our case, it will be a ClusterIP service:

cat < kubernetes/cluserip-service.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: stateless-flask

namespace: stateless-flask

spec:

selector:

app: stateless-flask

ports:

- name: http

protocol: TCP

port: 5000

targetPort: 5000

EOF

Apply the YAML file:

kubectl apply -f kubernetes/cluserip-service.yaml

Now, let's create the Ingress system.

We will use the Ingress NGINX Controller for Kubernetes, a popular open-source Ingress controller that uses NGINX. It's widely used and has a large community since it's maintained by the Kubernetes community.

To install it, we will use Helm.

ℹ️ Helm is a package manager for Kubernetes that simplifies the deployment and management of applications and services on Kubernetes clusters. It allows you to define, install, and upgrade Kubernetes applications using pre-configured packages called "charts."

Start by installing Helm on your workspace server:

curl \

https://raw.githubusercontent.com\

/helm/helm/master/scripts/get-helm-3 | \

bash

Add the Ingress NGINX Helm repository and install the Ingress controller:

# Add the ingress-nginx repository

helm repo add ingress-nginx \

https://kubernetes.github.io/ingress-nginx

# Update your local helm chart repository cache

helm repo update

# Install the Nginx Ingress controller

helm install nginx-ingress \

ingress-nginx/ingress-nginx \

--version 4.13.3

It is good practice to create a dedicated Namespace for the Ingress controller, but in our case, we will install it in the default Namespace. If you want to create a dedicated Namespace, it's possible by adding the --namespace and --create-namespace flags to the helm install command like so: helm install nginx-ingress ingress-nginx/ingress-nginx --namespace ingress-nginx --create-namespace

We can list the Pods and Services in the default Namespace to verify that the Ingress controller is running:

# Get the list of Pods

kubectl get pods -n default

# or kubectl get pods

# Get the list of Services

kubectl get services -n default

# or kubectl get services

Usually, after installing the Ingress controller, we would create an Ingress resource to define the routing rules. This is an example of an Ingress resource:

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: Cloud-Native Microservices With Kubernetes - 2nd Edition

A Comprehensive Guide to Building, Scaling, Deploying, Observing, and Managing Highly-Available Microservices in KubernetesEnroll now to unlock all content and receive all future updates for free.